Education System Barely Changed in 125 Years

The committee of 10 from the late 19th century put forth educational policies which can still be found in schools nationwide in 2019.

May 14, 2019

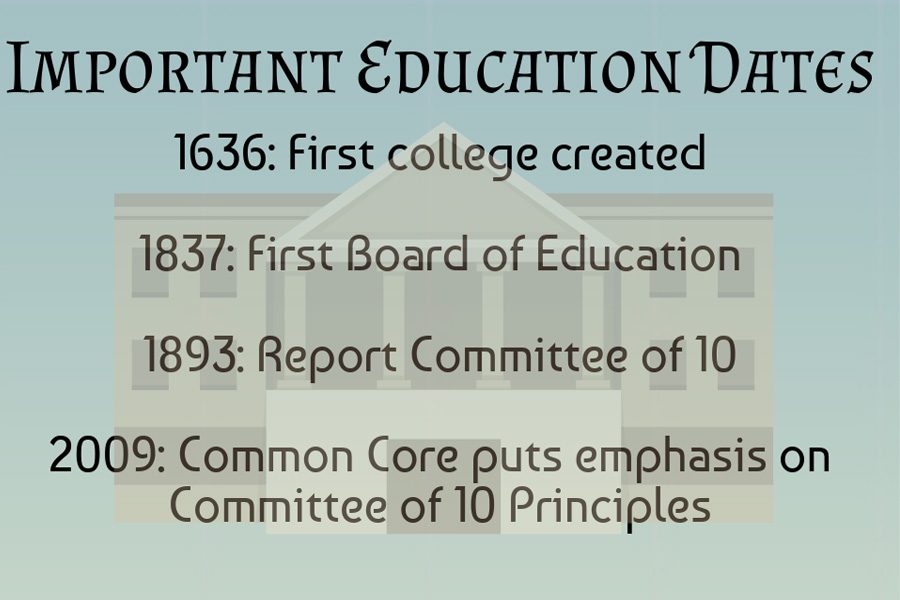

In 1893, the U.S. Education Commissioner, William Harris, was bent over a small table, finalizing his letter of transmittal to the Department of the Interior regarding the “Report of the Committee of 10 on Secondary Education.” He had labored alongside six college presidents and three high school headmasters for over a year to craft a uniform school curriculum based on the newest, progressive ideas. Just before signing, he penned the line, “I consider this to be the most important educational document published in the history of our country.”

Despite the constant testing, implementation and discarding of new educational theories–including MCPS’ recent restructuring of its curricula– the template created by the Committee of 10 is still upheld as the standard for American education, though it is frequently at odds with modern educational theories and the technology, economy and demographics of today’s society.

MCPS, like the rest of the country, is trying to update its curricula to keep up with changing demographics and technology. As these changes occur, one mostly unknown factor is the origins of the current curriculum, how it was shaped more than 125 years ago and how it continues to evolve.

The Committee of 10 dealt with education issues of its time. It was created to forge a standardized curriculum so colleges could have a uniform method of judging applicants. Recommendations that all students be taught the same content and in the same way regardless of their background or likely futures promoted the idea of education as a right and accounted for the surge in population in public schools due to an influx in immigration.

“It was very progressive for its time but what was modern then isn’t necessarily modern now… especially when you think about technology,” Professor of Education and Human Development at Georgia State University Chara Bochan said.

Since the publication of the report, technology and the racial diversity of the country have expanded. In 1893, the Committee of 10 could not have accounted for today’s population of non-white students in the public school system. The Hispanic population of the U.S. was so low then that it was not even enumerated in the 1890 census. These differences lead some to question whether a system created over a century ago is still relevant.

“Part of the problem is the system as a whole. The idea that we go to math for an hour, then social studies for an hour then science for an hour— it’s so contrary to everything else in life. Your life is not boxed one hour at a time. When we silo things like that, then it becomes harder for kids to see the relevance,” Director of Innovation at Future Ready Schools Tom Murray said.

The Committee of 10 was divided into nine subcommittees, each devoted to a core subject that the committee deemed important. Besides Greek and Latin, each of those core subjects–English, math, modern languages, the sciences, history, geography and natural history–are all subjects that students encounter on their road to graduation. They recommended a specific number of hours each week a student should spend on each subject, creating the block system of study that is found in schools today.

The philosophies of the Committee of 10 are evident in how core classes are taught. The Committee of 10 supported curricula comprised of learning through a combination of memorization and critical thinking. Beginning subjects such as math and English early and then building on them each year was principal in the philosophies of the Committee of 10.

They also recommended that each subject build off of knowledge from other subjects.

“For example, history should contribute to the study of English, and natural history should be correlated with language, drawing, literature and geography,” committee member and president of the University of Colorado James Baker wrote in his review of the recommendations of the Committee of 10.

Despite concerns over the continued relevance of the system, educational experts have faith in its adaptability and the continued necessity of core classes such as math and reading.

“Instead of simply going hog wild in one direction, learning math and science is what you need for a balanced education… The world was changing then and it’s still changing and so being able to understand things like math, like the supply and demand curve is useful in any economy,” Professor of Education Technology at Webster University Ralph Olliges said.

School systems, including MCPS, seek to adapt the system to the fast-paced changes of the information age by incorporating technologies such as promethean boards and chromebooks into classrooms. The State of Maryland also requires that all students take a technology class, promoting technological literacy in all students.

“That’s a conversation that people at very high levels in the education community are having right now. Everybody recognizes that we have a need to address that need for those [computer] skillsets when students graduate high school,” technology teacher Sean Gowen said.