Supreme Court Threatens Diversity in Higher Education

Since 1978’s landmark case, California v. Bakke, the Supreme Court repeatedly upheld universities’ ability to consider applicants’ race as one of many factors in admissions decisions. But the almost 45-year-long precedent is under fire as the U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative majority appears ready to throw out race-conscious policies with upcoming Harvard and the University of North Carolina cases.

But how might America’s colleges and universities change by a Supreme Court ruling that ends race-conscious admissions?

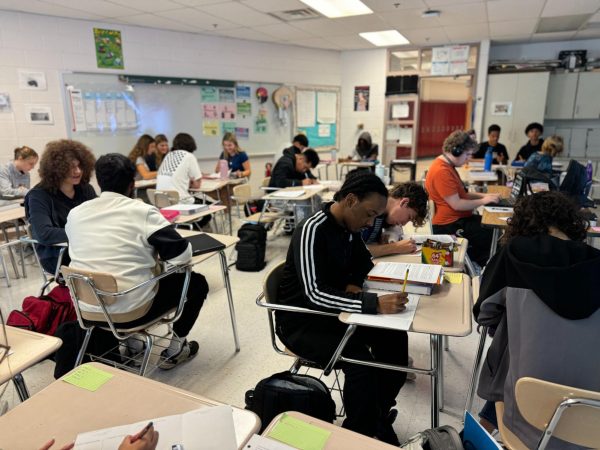

Schools argue that achieving racial diversity is almost impossible, especially at selective universities. Race-conscious admissions systems and investing in diversity efforts in universities are essential for a diverse student body.

“When you have diversity, not just in higher education but in all areas, it allows people to be able to get different perspectives,” Rockville High School (RHS) College and Career Coordinator Dwaine Brown said. “It creates a sense of community where there may not otherwise be community.”

Unfortunately, for much of American history, higher education was primarily reserved for the wealthy and predominantly white Americans. Strides in educational institutional diversity came in the 20th century with tools such as affirmative action, which consider race and ethnicity as part of a student’s holistic application.

Many first-generation, low-income, Black, Latinx, and other students of color, are sorely underrepresented in higher education and America’s top universities due to the country’s history of systemic inequity. Many groups and elite institutions continue to undermine access for students of color. According to school data, in the University of California, Berkeley’s 2022 freshman class of 6,750, only 229 were Black, nearly 3 percent.

The courts have long championed minority access to education, dating back to the 1954 landmark case Brown v. Board of Education, which ended segregated school systems. But the recent political climate and upcoming Harvard and North Carolina University cases cast doubt on this altogether.

“If I’m honest, we live in a country full of hypocrites. This is just the way this country has been for us now so I don’t expect [the Supreme Court] to have the best interests of the people at heart,” Brown said.

Affirmative action continues to be a point of contention in the conversation about college. For some, it represents the absolute minimum to address resource inequity. From others, it elicits cries of reverse discrimination. It is the fragile explosive elephant in the room. But the reality is that in an increasingly diverse nation, the education system poorly reflects it. Race-conscious admissions practices remain necessary to attain equal, accessible higher education.

“Arguably, socioeconomic factors are more of a telling point than race is. And it just so happens that those tend to correlate,” English teacher Dana Sato said.

However, for better or for worse, looking at race indicates a disturbing historical truth that a focus on income cannot: the centuries of systemic racism and underfunding. For instance, according to Princeton’s Journal of Public and International Affairs, students of color are less likely to be referred to “gifted and talented” programs, even when they satisfy the criteria.

So while the proponents of race-neutral admissions policies may sit smugly on their gilded seats and claim “equality,” maybe the better answer is equity. And equity does not mean neglecting historical and present systemic barriers.

Further, removing race as a factor in admissions decisions presents a major hypocrisy: legacies. Individuals with familial ties to an institution are still given an advantage in the admissions process, typically in elite U.S. colleges and universities.

“The idea that a student can get in just because mom or dad went there or because they had X amount of money is ludicrous,” Sato said. “Unless [the Supreme Court] does something about things like legacy admissions, unless they do something about how lower-income families are treated in the admissions process, then you can’t get rid of affirmative action.”

For some, the jeopardy of affirmative action was a long time coming, especially with the plague of red in the court following Trump’s three-justice appointments. But with the overturning of Roe v. Wade earlier in June 2022, affirmative action may be just another stone on their stampede, crushing decades of progress.

“I think we’ve been trending this way for a while,” Brown said. “We love to talk about how much the country has changed and how far along the country has come, but the reality is that we are not that far removed from separate water fountains.”